Curriculum Series, Part 2B: Another Assumption In which, dear reader, I continue to examine assumptions that hold districts and schools back from adopting high-quality curricula. The first assumption is here. Now ... Assumption #2: providing a curriculum disrespects teacher expertise/ teachers don't want or need a curriculum provided to them. My friend Kelly loved the principal at her first school, yet she left that building for another. Why? Her best friend was teaching at a school that used a structured literacy curriculum, and the kids were taking off as readers. Kelly wanted that for her students. She asked her principal to consider letting her use the same curriculum. “I don’t believe in teaching reading out of a box,” he said. So Kelly left and got a job at the same school as her friend. Her principal lost one of the best teachers I’ve ever seen in the 200+ classrooms I’ve visited all over the U.S. The principal’s belief—that providing teachers with a curriculum is “teaching out of a box”—is a common one. Writes Kathleen Porter-Magee (2017) “In education we have been conditioned to believe that mandating curriculum is akin to micromanaging an artist.” This point-of-view can lead districts to think they are doing teachers a favor by giving them unlimited “autonomy.” Even when lack of resources drives teacher dissatisfaction, as it did for my friend Kelly, we rarely talk about the positives that a strong curriculum can have, not just for students, but for teachers and their experiences. Providing teachers with high-quality materials can save them both time and money. A RAND study (2016) recently found that teachers rely heavily on materials that they develop or select themselves (99% of elementary ELA teachers do this, as well as using tools they’re provided). Teachers spend more than 12 hours per week on this work (Goldberg, 2016, cited in EdReports.org). Writes Robert Pondiscio (2016) “For teachers, it [having to develop their own curriculum] makes an already hard job nearly impossible to do well.” It also means that teachers often end up spending their own money to make sure they have the teaching resources they need. Doing such planning for ELA can be particularly time-consuming (well beyond twelve hours a week). When I’ve worked in curriculum development, I’ve often spent hours finding the right text for a lesson or assessment. When the right thing hasn’t been available, I’ve written pieces myself. This was my full time job, not something I had to do in the evenings on top of teaching a full day of classes. Requiring this work of teachers can help accelerate burn out, particularly for those new to the field. It’s likely this time crunch contributed to the fact that teachers identified “high-quality instructional materials and textbooks” as their NUMBER ONE (well, tied for first) funding priority in a Scholastic survey. It’s notable that materials didn’t even rank in principals’ Top 5 funding priorities, signaling a real disconnect in what teachers and leaders see as important. Principals and leaders may want to dig deeper if they believe teachers don't want or need high-quality resources. Another reason teachers may want high-quality materials? Shared resources can lead to robust, powerful collaboration. For example, when Detroit schools adopted EL ELA curriculum and Eureka Math, not only students showed growth--but teachers grew as well, through coming together in professional learning communities (Higgins, 2019) in which they supported one another through the curriculum shift. Some of those leaders then went on to support the teachers in Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools (EL Education, 2019), and in partnership with EL have shared free PowerPoints that can be used by teachers anywhere. Collaboration has even branched out nationally - check out the Facebook group where teachers are sharing their insights about EL curriculum, pointing each other toward resources (like those PowerPoints), and providing support through both excitement and challenge. I experienced this when I was moved into a first grade classroom in February of last year when a teacher unexpectedly left the school. There was no prescribed curriculum for first grade, so my partner teacher and I decided to start implementing EngageNY math and EL ELA curriculum. Our collaboration became much richer than it had before--no longer were we racing to find materials on the internet or designing new lessons. We were asking: how did that lesson go? Who got it? Who needs more support and why? How did you tweak this? Although we were two of the most experienced teachers on campus, having a curriculum didn’t bog us down or steal our creativity. It empowered us to focus on our students in an even deeper way. Finally, high-quality curriculum can build feelings of efficacy when we see our kids achieving at high levels, our districts improving, and our work paying off. This was why my friend Kelly ultimately had to leave her first school -- to grow into her best professional self. Her curriculum helped her to build capacity, and she became a stronger teacher for it. Check out this incredible thread (especially the inspiring videos from @kyairb) for more examples of how powerful curriculum can play out for kids and teachers. Says @kyairb: "Absolutely. Your kids can do it.... I'm a really good teacher. I know what I'm capable of doing, and I know that I'm capable of committing myself to a curriculum that builds knowledge." Resources, collaboration, feelings of efficacy ... sounds great! Despite the positives that a curriculum adoption can bring, many teachers still find curriculum change to be a miserable experience. This is often an issue of implementation, rather than the curriculum itself. I’m going to write more about what I’ve learned about implementation later in this series, but I did want to mention one thing. Too often, teachers feel disrespected during curriculum change because there is a focus on fidelity to the curriculum without honoring the lived experience of teachers and their students. Take one example: Several of my friends worked at a charter network where they were given a high-quality curriculum with interesting texts and lots of support; no deviation from the script was accepted. Implementation was a constant source of frustration. One of my friends was the lead teacher and was still evaluated on her fidelity, rather than effectiveness. She wanted curriculum and feedback to help her grow, but she didn’t want to simply become a script reader. While it’s important to implement a new curriculum without diluting its power, there is an alternative to ”fidelity:” integrity. Writes Paul LeMahieu (2011): “This idea of integrity in implementation allows for programmatic expression in a manner that remains true to essential empirically-warranted ideas while being responsive to varied conditions and contexts.” In other words: you keep the well-researched practice in the curriculum, while using your knowledge of context to maximize the impact of the curriculum and make it relevant for your students. If we keep our focus on implementation with integrity, we can experience the benefits of high-quality curriculum without many of the downsides that cause people to fear “teaching out of a box.” Note: This is the third in a series on the practical side of implementing high-quality curricula. Part 1: The Power of a Quality Curriculum Part 2A: Assumptions Part 2B: Another Assumption Part 2C: One More Assumption Part 3: Choosing a Quality Curriculum

3 Comments

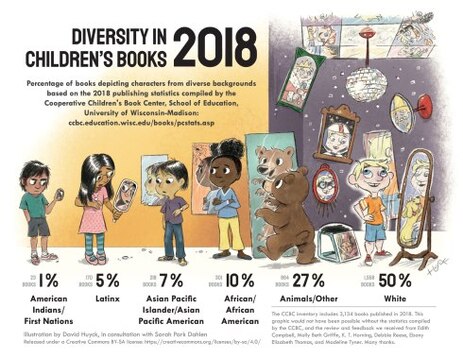

Curriculum Series, Part 2A: Assumptions November 6th, 2018—the 4th grade classroom was abuzz with discussion as students took turns at the mock voting booth, deciding whether Beto O’Rourke or Ted Cruz should be our state’s senator—just like adults were doing down the hall.* The classroom was hung with posters advocating for voting, and a stack of essays sat on my desk, arguing why voting was important. When the assistant principal came in, the students were eager to tell her how many Americans didn’t vote, and why that surprised them, given the long fight for suffrage for women and people of color. You might assume that kind of real-world, time-embedded teaching couldn’t be done with a district-mandated curriculum. But of course (spoiler alert), it was. The RAND Corporation (Kaufman, Tosh, & Mattox, 2019) recently found that only 7% of elementary ELA teachers are regularly using high-quality curricular materials. Why is that? Over the past several years advocating for curriculum changes, I’ve heard all kinds of push back to adopting these curricula, much of it based on assumptions about instituting centralized curriculum. The three that I have encountered most? 1) A centralized curriculum is boring/irrelevant; 2) Providing a curriculum disrespects teacher expertise; and 3) Common Core-aligned curricula are "too rigorous" for our striving readers. I kept hearing these things as I worked to change our district’s literacy practices, and I began to doubt my advocacy for this change. I decided I had to pressure test some of these assumptions myself. So, after 11 years of coaching and literacy leadership, I spent a year full-time in the classroom. I ended up teaching fourth and first grades, each for about half a year (due to one of those shake-ups that tend to happen when a staff member leaves suddenly). In this post and the next, I’ll share my thoughts about what I’ve learned about these three assumptions. What I Learned About Curriculum, Relevance, and Representation First, let’s address the white elephant in the reading room: children’s literature has a long way to go before the characters look like the kids in America’s schools. While approximately 51% of public school students are children of color (NCES, 2019) the number of characters of color in children’s literature stands at 23% (CCBC in Huyck & Dahlen, 2019)--fewer than the percentage of animal/other characters. This weakness impacts curricular materials, of course. The Coalition for Educational Justice (2019) looked at ten popular curricula and book lists used in the New York City area, including several that are highly-rated for standards alignment on EdReports. They examined the number of texts by authors of color, as well as the characters on text covers. They found a situation slightly better than the publishing world at large, with 33% of cover characters representing children of color, 35% White children, and yes … 32% animals. Representation was particularly low for Latinx, Asian, and Indigenous characters. This means that no matter what teaching methodology we ascribe to, as teachers we need to keep searching for ways to make our teaching more culturally relevant. However, the study linked above found that some of the weakest representation of children of color was found in the curricula or booklists that are often used by teachers who focus on teaching through students’ self-selected reading. High-quality curricula can get us started from a slightly stronger place than relying on the classroom library the district purchases for us. In addition, many of the developers of newer curricula have student interest and relevance on their minds. For example, the folks at Great Minds were willing to work with Baltimore City Schools to increase the relevance of their With & Wisdom curriculum to better connect to the community (Loftus & Sappington, 2019). Open Educational Resources (OER) are free and online, allowing developers to be more responsive to users’ needs. Often, these resources are adaptable for teachers who want to tailor instruction to reflect their students’ communities and identities. It was through the use of an adaptable OER that I was able to craft the election day experience in my fourth grade classroom. Our module centered on creating change, with a focus on battling for suffrage. I had planned a similar unit from scratch during the 2004 presidential election, but having the foundation of a trustworthy, high-quality module made the planning easier. Because the scope of the module had been laid out, I was able to look through the entire thing and determine where I wanted to add or subtract material to increase representation and relevance. Given that most of my students were Latinx, many born in Mexico, it was critical to connect to the political events of the day, which we often discussed in class. We identified issues the students cared about, then read quotes from the Senate candidates so students could determine who they would “vote” for. On election day, they were knowledgeable about the most important issues facing them in a way that wouldn’t have been possible without the rich knowledge built through the curriculum. Having that framework also gave me the time to plan to connect the lessons to my students in a way that I wouldn’t have been able to if I’d had to scramble to find materials and texts. So, yes, standardized curriculum can be relevant and engaging … when the teacher is allowed the freedom to tweak the lessons, and has the knowledge to keep the integrity of the program’s alignment with standards and research. And that has to do with implementation… more on that coming up soon. * The kids picked Beto in a landslide. This is the second in a series on the practical side of implementing high-quality curricula. Part 1: The Power of a Quality Curriculum Part 2A: Assumptions Part 2B: More Assumptions Part 3: Choosing a Quality Curriculum Part 4: Implementing a Quality Curriculum (Coach/Admin Edition) Part 5: Implementing a Quality Curriculum (Teacher Edition) Notes: Note 1: I had planned ONE post on curriculum assumptions, but this one ended up being a bit longer than I intended. I’ll address two more assumptions coming up. Note 2: I had originally planned to talk about curriculum “myths,” but decided to change to “assumptions” because myths implies these beliefs aren’t true. I think these assumptions do have seeds of truth in them -- it’s just that the seeds are planted through implementation issues, rather than by the curricula themselves. Implementation will be coming up. Note 3: That cool graphic is free to use through the Creative Commons License, as long as the full citation is provided. Here’s the full citation! Huyck, David and Sarah Park Dahlen. (2019 June 19). Diversity in Children’s Books 2018. sarahpark.com blog. Created in consultation with Edith Campbell, Molly Beth Griffin, K. T. Horning, Debbie Reese, Ebony Elizabeth Thomas, and Madeline Tyner, with statistics compiled by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center, School of Education, University of Wisconsin-Madison: http://ccbc.education.wisc.edu/books/pcstats.asp. Retrieved from https://readingspark.wordpress.com/2019/06/19/picture-this-diversity-in-childrens-books-2018-infographic/. |

Click the categories below for entries on specific topics.

AuthorCatlin Goodrow, M.A.T Archives

December 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed