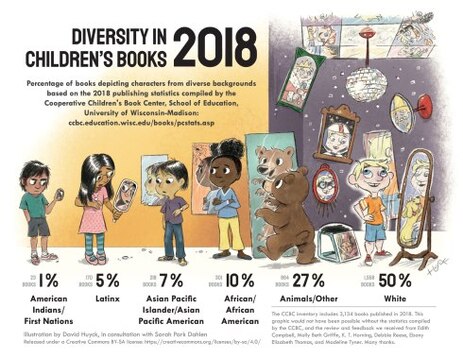

Curriculum Series, Part 2A: Assumptions November 6th, 2018—the 4th grade classroom was abuzz with discussion as students took turns at the mock voting booth, deciding whether Beto O’Rourke or Ted Cruz should be our state’s senator—just like adults were doing down the hall.* The classroom was hung with posters advocating for voting, and a stack of essays sat on my desk, arguing why voting was important. When the assistant principal came in, the students were eager to tell her how many Americans didn’t vote, and why that surprised them, given the long fight for suffrage for women and people of color. You might assume that kind of real-world, time-embedded teaching couldn’t be done with a district-mandated curriculum. But of course (spoiler alert), it was. The RAND Corporation (Kaufman, Tosh, & Mattox, 2019) recently found that only 7% of elementary ELA teachers are regularly using high-quality curricular materials. Why is that? Over the past several years advocating for curriculum changes, I’ve heard all kinds of push back to adopting these curricula, much of it based on assumptions about instituting centralized curriculum. The three that I have encountered most? 1) A centralized curriculum is boring/irrelevant; 2) Providing a curriculum disrespects teacher expertise; and 3) Common Core-aligned curricula are "too rigorous" for our striving readers. I kept hearing these things as I worked to change our district’s literacy practices, and I began to doubt my advocacy for this change. I decided I had to pressure test some of these assumptions myself. So, after 11 years of coaching and literacy leadership, I spent a year full-time in the classroom. I ended up teaching fourth and first grades, each for about half a year (due to one of those shake-ups that tend to happen when a staff member leaves suddenly). In this post and the next, I’ll share my thoughts about what I’ve learned about these three assumptions. What I Learned About Curriculum, Relevance, and Representation First, let’s address the white elephant in the reading room: children’s literature has a long way to go before the characters look like the kids in America’s schools. While approximately 51% of public school students are children of color (NCES, 2019) the number of characters of color in children’s literature stands at 23% (CCBC in Huyck & Dahlen, 2019)--fewer than the percentage of animal/other characters. This weakness impacts curricular materials, of course. The Coalition for Educational Justice (2019) looked at ten popular curricula and book lists used in the New York City area, including several that are highly-rated for standards alignment on EdReports. They examined the number of texts by authors of color, as well as the characters on text covers. They found a situation slightly better than the publishing world at large, with 33% of cover characters representing children of color, 35% White children, and yes … 32% animals. Representation was particularly low for Latinx, Asian, and Indigenous characters. This means that no matter what teaching methodology we ascribe to, as teachers we need to keep searching for ways to make our teaching more culturally relevant. However, the study linked above found that some of the weakest representation of children of color was found in the curricula or booklists that are often used by teachers who focus on teaching through students’ self-selected reading. High-quality curricula can get us started from a slightly stronger place than relying on the classroom library the district purchases for us. In addition, many of the developers of newer curricula have student interest and relevance on their minds. For example, the folks at Great Minds were willing to work with Baltimore City Schools to increase the relevance of their With & Wisdom curriculum to better connect to the community (Loftus & Sappington, 2019). Open Educational Resources (OER) are free and online, allowing developers to be more responsive to users’ needs. Often, these resources are adaptable for teachers who want to tailor instruction to reflect their students’ communities and identities. It was through the use of an adaptable OER that I was able to craft the election day experience in my fourth grade classroom. Our module centered on creating change, with a focus on battling for suffrage. I had planned a similar unit from scratch during the 2004 presidential election, but having the foundation of a trustworthy, high-quality module made the planning easier. Because the scope of the module had been laid out, I was able to look through the entire thing and determine where I wanted to add or subtract material to increase representation and relevance. Given that most of my students were Latinx, many born in Mexico, it was critical to connect to the political events of the day, which we often discussed in class. We identified issues the students cared about, then read quotes from the Senate candidates so students could determine who they would “vote” for. On election day, they were knowledgeable about the most important issues facing them in a way that wouldn’t have been possible without the rich knowledge built through the curriculum. Having that framework also gave me the time to plan to connect the lessons to my students in a way that I wouldn’t have been able to if I’d had to scramble to find materials and texts. So, yes, standardized curriculum can be relevant and engaging … when the teacher is allowed the freedom to tweak the lessons, and has the knowledge to keep the integrity of the program’s alignment with standards and research. And that has to do with implementation… more on that coming up soon. * The kids picked Beto in a landslide. This is the second in a series on the practical side of implementing high-quality curricula. Part 1: The Power of a Quality Curriculum Part 2A: Assumptions Part 2B: More Assumptions Part 3: Choosing a Quality Curriculum Part 4: Implementing a Quality Curriculum (Coach/Admin Edition) Part 5: Implementing a Quality Curriculum (Teacher Edition) Notes: Note 1: I had planned ONE post on curriculum assumptions, but this one ended up being a bit longer than I intended. I’ll address two more assumptions coming up. Note 2: I had originally planned to talk about curriculum “myths,” but decided to change to “assumptions” because myths implies these beliefs aren’t true. I think these assumptions do have seeds of truth in them -- it’s just that the seeds are planted through implementation issues, rather than by the curricula themselves. Implementation will be coming up. Note 3: That cool graphic is free to use through the Creative Commons License, as long as the full citation is provided. Here’s the full citation! Huyck, David and Sarah Park Dahlen. (2019 June 19). Diversity in Children’s Books 2018. sarahpark.com blog. Created in consultation with Edith Campbell, Molly Beth Griffin, K. T. Horning, Debbie Reese, Ebony Elizabeth Thomas, and Madeline Tyner, with statistics compiled by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center, School of Education, University of Wisconsin-Madison: http://ccbc.education.wisc.edu/books/pcstats.asp. Retrieved from https://readingspark.wordpress.com/2019/06/19/picture-this-diversity-in-childrens-books-2018-infographic/.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Click the categories below for entries on specific topics.

AuthorCatlin Goodrow, M.A.T Archives

December 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed