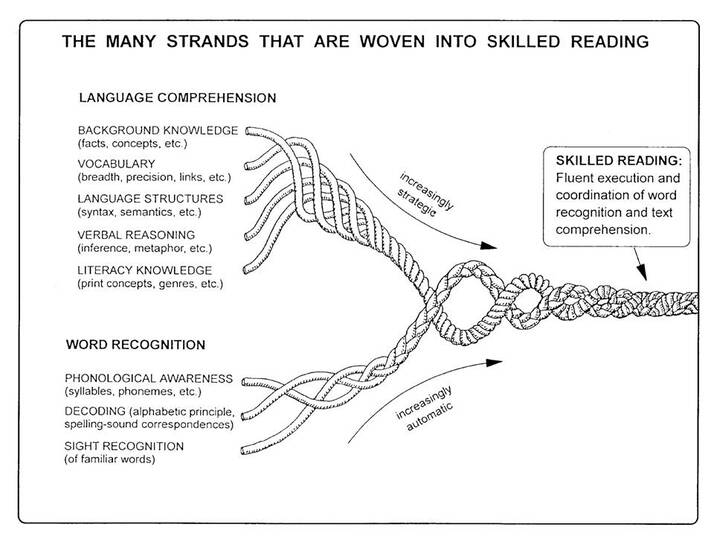

Curriculum Series, Part 3 Scarborough's reading rope (2001). Learn it, love it, sleep with a copy under your pillow. Scarborough's reading rope (2001). Learn it, love it, sleep with a copy under your pillow. Lately, I’ve responded to many questions, both online and in-person, about how to choose ELA curriculum. After all, it’s that time of year, when education leaders start thinking about the next school year and how they might improve student outcomes. (At least, I hope that’s what they are thinking about. They probably are not thinking that they have millions of dollars just lying around and new books might be nice. But you never know.) The curriculum selection process can be fraught—you want the best for kids, to make teachers’ lives easier, and to stay in budget. And even with a strong process, you’ll probably find that some people are just going to complain, no matter what you end up with. Still, I’ve learned a few things over the years that can help make the decision a little easier. Get grounded in the evidence In the past (and … probably today, let’s face it), curriculum selection looked like this: the district would put out a bunch of samples provided by publishing companies, invite teachers to look at them and give feedback, and then pick something that looked pretty or provided the best value. Those publishing reps are still out there with their samples, and a proliferation of online tools may catch your eye. With all those cute materials out there, it’s important to focus on what goes into skilled reading: decoding x language comprehension, aka the Simple View of Reading (proposed by Gough and Tunmer in 1986; you can find a good summary in the first third of this article). Scarborough’s “reading rope” (2001) further broke down each of those pieces. When you have the simple view in mind, looking at curricular materials becomes much clearer. Materials that don’t teach decoding systematically and explicitly, or don’t build language comprehension (which includes robust background knowledge), won’t give all children the opportunity to become proficient readers. There are many beautifully-packaged programs that do a bang-up job on one side of the equation, but not the other (and some that don’t do either well). You want to find materials that do both. Use free resources Finding a curriculum that teaches all parts of reading well may sound daunting, particularly if you’re a teacher or leader who has, you know, a few other things on your plate. Luckily, organizations have done the review work for us. EdReports and Louisiana Believes have some of the most complete reports on materials quality. Your state department of education may also have curriculum adoption materials available on their websites, such as rubrics or their own reports. However, be sure to crosscheck these with the sites listed above. I once did a curriculum review for a small charter school, and found that none of the curricula recommended by their state had been rated as aligned to the Common Core State Standards by EdReports. States often have other interests driving their decisions that go beyond educational best practices (as a recent New York Times investigation of textbooks showed). Put together a team Don’t deputize one person to choose the curriculum—and if you are the person who has already been deputized, this advice goes double. Put together a committee that will do the preliminary work of narrowing down choices to two or three, before presenting these to the broader group of stakeholders. Ideally, this team should consist of both new and experienced teachers, administrators, interventionists, and family or community members. Why include the community? Because they will be able to highlight the types of texts and experiences they want for their children. Many curriculum developers are actively working to increase the cultural relevance of their materials, but there is still much work to do in that area. By including community and families, you increase the chances of choosing curricular materials that will provide your students with both windows and mirrors. Make sure administrators are on board. No, really on board. I once participated in a curriculum selection process that was truly teacher-driven; in fact, teachers initiated the process and I supported them as literacy specialist. It was the sort of grassroots change that we often extol in education … and it was ultimately a failure, because even though administrators were brought into the process at various points, they didn’t have the deep understanding of reading science about how kids learn to read. Both your committee and all administrators need to be grounded in what makes great literacy teaching, particularly as this can look much different from the standards-based, skills-focused teaching that works in many other subjects. Unless administrators are prepared to work shoulder-to-shoulder with teachers in implementing a new curriculum, things can get very messy, very quickly. While there’s no easy way to find the right curriculum for your school or district, having a strategic, inclusive process will help set a firm foundation for the really fun part … implementation! (Coming up!) Note: This is the third (really, the fourth) in a series on the practical side of implementing high-quality curricula. Part 1: The Power of a Quality Curriculum Part 2A: Assumptions Part 2B: Another Assumption Part 2C: One More Assumption Part 3: Choosing a Quality Curriculum

0 Comments

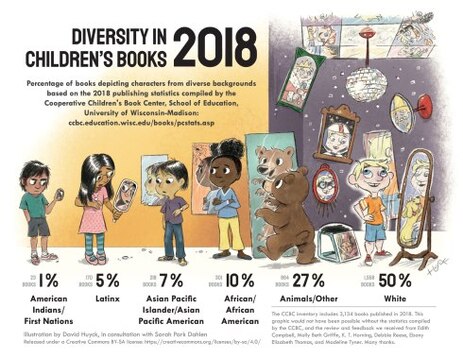

Curriculum Series, Part 2B: Another Assumption In which, dear reader, I continue to examine assumptions that hold districts and schools back from adopting high-quality curricula. The first assumption is here. Now ... Assumption #2: providing a curriculum disrespects teacher expertise/ teachers don't want or need a curriculum provided to them. My friend Kelly loved the principal at her first school, yet she left that building for another. Why? Her best friend was teaching at a school that used a structured literacy curriculum, and the kids were taking off as readers. Kelly wanted that for her students. She asked her principal to consider letting her use the same curriculum. “I don’t believe in teaching reading out of a box,” he said. So Kelly left and got a job at the same school as her friend. Her principal lost one of the best teachers I’ve ever seen in the 200+ classrooms I’ve visited all over the U.S. The principal’s belief—that providing teachers with a curriculum is “teaching out of a box”—is a common one. Writes Kathleen Porter-Magee (2017) “In education we have been conditioned to believe that mandating curriculum is akin to micromanaging an artist.” This point-of-view can lead districts to think they are doing teachers a favor by giving them unlimited “autonomy.” Even when lack of resources drives teacher dissatisfaction, as it did for my friend Kelly, we rarely talk about the positives that a strong curriculum can have, not just for students, but for teachers and their experiences. Providing teachers with high-quality materials can save them both time and money. A RAND study (2016) recently found that teachers rely heavily on materials that they develop or select themselves (99% of elementary ELA teachers do this, as well as using tools they’re provided). Teachers spend more than 12 hours per week on this work (Goldberg, 2016, cited in EdReports.org). Writes Robert Pondiscio (2016) “For teachers, it [having to develop their own curriculum] makes an already hard job nearly impossible to do well.” It also means that teachers often end up spending their own money to make sure they have the teaching resources they need. Doing such planning for ELA can be particularly time-consuming (well beyond twelve hours a week). When I’ve worked in curriculum development, I’ve often spent hours finding the right text for a lesson or assessment. When the right thing hasn’t been available, I’ve written pieces myself. This was my full time job, not something I had to do in the evenings on top of teaching a full day of classes. Requiring this work of teachers can help accelerate burn out, particularly for those new to the field. It’s likely this time crunch contributed to the fact that teachers identified “high-quality instructional materials and textbooks” as their NUMBER ONE (well, tied for first) funding priority in a Scholastic survey. It’s notable that materials didn’t even rank in principals’ Top 5 funding priorities, signaling a real disconnect in what teachers and leaders see as important. Principals and leaders may want to dig deeper if they believe teachers don't want or need high-quality resources. Another reason teachers may want high-quality materials? Shared resources can lead to robust, powerful collaboration. For example, when Detroit schools adopted EL ELA curriculum and Eureka Math, not only students showed growth--but teachers grew as well, through coming together in professional learning communities (Higgins, 2019) in which they supported one another through the curriculum shift. Some of those leaders then went on to support the teachers in Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools (EL Education, 2019), and in partnership with EL have shared free PowerPoints that can be used by teachers anywhere. Collaboration has even branched out nationally - check out the Facebook group where teachers are sharing their insights about EL curriculum, pointing each other toward resources (like those PowerPoints), and providing support through both excitement and challenge. I experienced this when I was moved into a first grade classroom in February of last year when a teacher unexpectedly left the school. There was no prescribed curriculum for first grade, so my partner teacher and I decided to start implementing EngageNY math and EL ELA curriculum. Our collaboration became much richer than it had before--no longer were we racing to find materials on the internet or designing new lessons. We were asking: how did that lesson go? Who got it? Who needs more support and why? How did you tweak this? Although we were two of the most experienced teachers on campus, having a curriculum didn’t bog us down or steal our creativity. It empowered us to focus on our students in an even deeper way. Finally, high-quality curriculum can build feelings of efficacy when we see our kids achieving at high levels, our districts improving, and our work paying off. This was why my friend Kelly ultimately had to leave her first school -- to grow into her best professional self. Her curriculum helped her to build capacity, and she became a stronger teacher for it. Check out this incredible thread (especially the inspiring videos from @kyairb) for more examples of how powerful curriculum can play out for kids and teachers. Says @kyairb: "Absolutely. Your kids can do it.... I'm a really good teacher. I know what I'm capable of doing, and I know that I'm capable of committing myself to a curriculum that builds knowledge." Resources, collaboration, feelings of efficacy ... sounds great! Despite the positives that a curriculum adoption can bring, many teachers still find curriculum change to be a miserable experience. This is often an issue of implementation, rather than the curriculum itself. I’m going to write more about what I’ve learned about implementation later in this series, but I did want to mention one thing. Too often, teachers feel disrespected during curriculum change because there is a focus on fidelity to the curriculum without honoring the lived experience of teachers and their students. Take one example: Several of my friends worked at a charter network where they were given a high-quality curriculum with interesting texts and lots of support; no deviation from the script was accepted. Implementation was a constant source of frustration. One of my friends was the lead teacher and was still evaluated on her fidelity, rather than effectiveness. She wanted curriculum and feedback to help her grow, but she didn’t want to simply become a script reader. While it’s important to implement a new curriculum without diluting its power, there is an alternative to ”fidelity:” integrity. Writes Paul LeMahieu (2011): “This idea of integrity in implementation allows for programmatic expression in a manner that remains true to essential empirically-warranted ideas while being responsive to varied conditions and contexts.” In other words: you keep the well-researched practice in the curriculum, while using your knowledge of context to maximize the impact of the curriculum and make it relevant for your students. If we keep our focus on implementation with integrity, we can experience the benefits of high-quality curriculum without many of the downsides that cause people to fear “teaching out of a box.” Note: This is the third in a series on the practical side of implementing high-quality curricula. Part 1: The Power of a Quality Curriculum Part 2A: Assumptions Part 2B: Another Assumption Part 2C: One More Assumption Part 3: Choosing a Quality Curriculum Curriculum Series, Part 2A: Assumptions November 6th, 2018—the 4th grade classroom was abuzz with discussion as students took turns at the mock voting booth, deciding whether Beto O’Rourke or Ted Cruz should be our state’s senator—just like adults were doing down the hall.* The classroom was hung with posters advocating for voting, and a stack of essays sat on my desk, arguing why voting was important. When the assistant principal came in, the students were eager to tell her how many Americans didn’t vote, and why that surprised them, given the long fight for suffrage for women and people of color. You might assume that kind of real-world, time-embedded teaching couldn’t be done with a district-mandated curriculum. But of course (spoiler alert), it was. The RAND Corporation (Kaufman, Tosh, & Mattox, 2019) recently found that only 7% of elementary ELA teachers are regularly using high-quality curricular materials. Why is that? Over the past several years advocating for curriculum changes, I’ve heard all kinds of push back to adopting these curricula, much of it based on assumptions about instituting centralized curriculum. The three that I have encountered most? 1) A centralized curriculum is boring/irrelevant; 2) Providing a curriculum disrespects teacher expertise; and 3) Common Core-aligned curricula are "too rigorous" for our striving readers. I kept hearing these things as I worked to change our district’s literacy practices, and I began to doubt my advocacy for this change. I decided I had to pressure test some of these assumptions myself. So, after 11 years of coaching and literacy leadership, I spent a year full-time in the classroom. I ended up teaching fourth and first grades, each for about half a year (due to one of those shake-ups that tend to happen when a staff member leaves suddenly). In this post and the next, I’ll share my thoughts about what I’ve learned about these three assumptions. What I Learned About Curriculum, Relevance, and Representation First, let’s address the white elephant in the reading room: children’s literature has a long way to go before the characters look like the kids in America’s schools. While approximately 51% of public school students are children of color (NCES, 2019) the number of characters of color in children’s literature stands at 23% (CCBC in Huyck & Dahlen, 2019)--fewer than the percentage of animal/other characters. This weakness impacts curricular materials, of course. The Coalition for Educational Justice (2019) looked at ten popular curricula and book lists used in the New York City area, including several that are highly-rated for standards alignment on EdReports. They examined the number of texts by authors of color, as well as the characters on text covers. They found a situation slightly better than the publishing world at large, with 33% of cover characters representing children of color, 35% White children, and yes … 32% animals. Representation was particularly low for Latinx, Asian, and Indigenous characters. This means that no matter what teaching methodology we ascribe to, as teachers we need to keep searching for ways to make our teaching more culturally relevant. However, the study linked above found that some of the weakest representation of children of color was found in the curricula or booklists that are often used by teachers who focus on teaching through students’ self-selected reading. High-quality curricula can get us started from a slightly stronger place than relying on the classroom library the district purchases for us. In addition, many of the developers of newer curricula have student interest and relevance on their minds. For example, the folks at Great Minds were willing to work with Baltimore City Schools to increase the relevance of their With & Wisdom curriculum to better connect to the community (Loftus & Sappington, 2019). Open Educational Resources (OER) are free and online, allowing developers to be more responsive to users’ needs. Often, these resources are adaptable for teachers who want to tailor instruction to reflect their students’ communities and identities. It was through the use of an adaptable OER that I was able to craft the election day experience in my fourth grade classroom. Our module centered on creating change, with a focus on battling for suffrage. I had planned a similar unit from scratch during the 2004 presidential election, but having the foundation of a trustworthy, high-quality module made the planning easier. Because the scope of the module had been laid out, I was able to look through the entire thing and determine where I wanted to add or subtract material to increase representation and relevance. Given that most of my students were Latinx, many born in Mexico, it was critical to connect to the political events of the day, which we often discussed in class. We identified issues the students cared about, then read quotes from the Senate candidates so students could determine who they would “vote” for. On election day, they were knowledgeable about the most important issues facing them in a way that wouldn’t have been possible without the rich knowledge built through the curriculum. Having that framework also gave me the time to plan to connect the lessons to my students in a way that I wouldn’t have been able to if I’d had to scramble to find materials and texts. So, yes, standardized curriculum can be relevant and engaging … when the teacher is allowed the freedom to tweak the lessons, and has the knowledge to keep the integrity of the program’s alignment with standards and research. And that has to do with implementation… more on that coming up soon. * The kids picked Beto in a landslide. This is the second in a series on the practical side of implementing high-quality curricula. Part 1: The Power of a Quality Curriculum Part 2A: Assumptions Part 2B: More Assumptions Part 3: Choosing a Quality Curriculum Part 4: Implementing a Quality Curriculum (Coach/Admin Edition) Part 5: Implementing a Quality Curriculum (Teacher Edition) Notes: Note 1: I had planned ONE post on curriculum assumptions, but this one ended up being a bit longer than I intended. I’ll address two more assumptions coming up. Note 2: I had originally planned to talk about curriculum “myths,” but decided to change to “assumptions” because myths implies these beliefs aren’t true. I think these assumptions do have seeds of truth in them -- it’s just that the seeds are planted through implementation issues, rather than by the curricula themselves. Implementation will be coming up. Note 3: That cool graphic is free to use through the Creative Commons License, as long as the full citation is provided. Here’s the full citation! Huyck, David and Sarah Park Dahlen. (2019 June 19). Diversity in Children’s Books 2018. sarahpark.com blog. Created in consultation with Edith Campbell, Molly Beth Griffin, K. T. Horning, Debbie Reese, Ebony Elizabeth Thomas, and Madeline Tyner, with statistics compiled by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center, School of Education, University of Wisconsin-Madison: http://ccbc.education.wisc.edu/books/pcstats.asp. Retrieved from https://readingspark.wordpress.com/2019/06/19/picture-this-diversity-in-childrens-books-2018-infographic/. Curriculum Series, Part 1 [Meme showing LeBron James. "You say you care about outcomes, but your curriculum is from Pinterest."] [Meme showing LeBron James. "You say you care about outcomes, but your curriculum is from Pinterest."] This is the first in a series on the practical side of implementing high-quality curricula. Part 1: The Power of a Quality Curriculum Part 2A: Assumptions & 2B: More Assumptions Part 3: Choosing a Quality Curriculum Part 4: Implementing a Quality Curriculum (Coach/Admin Edition) Part 5: Implementing a Quality Curriculum (Teacher Edition) When I was a kid, my family moved a lot. I went to four different schools between kinder and 4th grade. I remember coming home one day from that fourth school, and telling my mom, “We’re learning about bees again. Why do we study bees every year?” You see, I was under the logical (yet, false) assumption that someone (maybe the president?) had determined what a kid should learn every year -- and that bees only needed to be studied once in elementary school. Don’t get me wrong, bees are fascinating. It’s just that there are other insects deserving of study -- not to mention all the other animals. I know a lot more about education now, but as Natalie Wexler points out in The Knowledge Gap (2019), our educational standards describe many processes, skills, and strategies that students are supposed to learn, but are vague on the content that students should be processing and strategizing about. That’s where having a high-quality curriculum can shine a light. When I say “high-quality” curriculum, I am talking about those literacy curricula that align with the current best evidence about how children learn to read. These curricula are explicit and systematic in teaching decoding, and they intentionally build world knowledge. They also avoid teaching counterproductive strategies, like the three-cueing system. (Check out edreports.org for more information about excellent curricula.) Such curricula are powerful in a way that the old-school basal programs were not. As a literacy coach, curriculum coordinator and teacher, I’ve seen three main ways that power manifests: A high-quality curriculum is coherent. What my little fourth grade heart desired was coherence -- a curriculum that put a stake in the ground about what should be learned each year, how that knowledge should build, and how it all links together. According to cognitive scientist Daniel Willingham (2006), that coherence isn’t just elegant, but helps us learn: “A rich network of associations makes memory strong: New material is more likely to be remembered if it is related to what is already in memory.” A colleague and I saw this in action last year, when we tested out a module from the EL Education first grade curriculum. The module topic was sun, moon, and stars. Because of the coherent, systematic knowledge-building, our first graders were able to articulate deep understanding of why we have day/night and seasons. These same concepts were ones that our fifth grade students were struggling to comprehend in science class. A high-quality curriculum also drives equity. Recently, TNTP (2018) found that out of 180 hours of instruction, 133 hours are spent on activities that are not on grade level. Almost 40% of the study classrooms with a majority of students of color had NO assignments on grade level, compared to 12% of classrooms with a majority of White students. This is, frankly, appalling. However, many teachers aren’t given the resources to align their instruction to a high bar of excellence. For example, I witnessed a lesson in which the teacher followed the district-provided curriculum, trusting that she was given a quality resource. The curriculum did not align to grade level standards for complex text, and one of the second grade vocabulary words was basketball. Compare that to vocabulary words in a highly-rated, Common Core-aligned curriculum for second grade: compassion, visible, and respond. In which classroom would children be on the road to being college- and career-ready? Finally, a high-quality curriculum can build teacher capacity. A colleague of mine says, “Teaching a good curriculum is the best professional development.” It can help us understand standards, teach us new pedagogical methods, and introduce us to new texts and topics. More importantly, it can shift the teacher’s time and focus away from scrambling for materials, to diving deep into lessons and considering how students will be impacted. We can unleash this power in classrooms throughout our country. However… a series of myths about curriculum persist. I’ll discuss those in Part 2. |

Click the categories below for entries on specific topics.

AuthorCatlin Goodrow, M.A.T Archives

December 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed