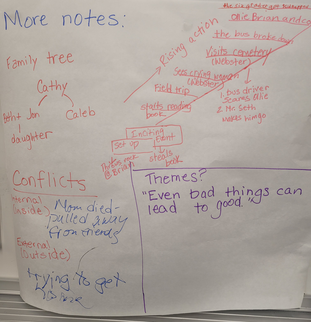

Our ongoing text map for Small Spaces. Our ongoing text map for Small Spaces. I was a few minutes late for my fifth grade reading group and rushed in, preparing to apologize to my students; I expected them to be sitting and twiddling their thumbs. Instead, one of the students had taken my usual place, passed out the books, and called on a peer to start reading. They just couldn’t wait another minute to dive back into the novel they were reading. I sat down in one of the chairs, picked up a book, and joined in. Later, we continued a lively, ongoing debate. The question: who was the terrifying “Smiling Man” in Katherine Arden’s Small Spaces? We were building a list of which characters might be the Smiling Man, and each student had their own personal theories. They added their thoughts to a sprawling text map we’d been keeping on sheets of butcher paper taped together. This excitement for learning is exactly what we hope for our students, and was in sharp contrast to the students’ attitudes at the beginning of the year. All five had been reluctant readers who claimed that reading was boring and dragged their feet when it was time to come to their reading lesson. For years, the conventional wisdom has been that we can spur reading growth and love of reading by providing copious amounts of reading time along with books that students can already read proficiently. Because, in this context, students are all reading different texts, the teaching comes in the form of generally-applicable mini-lessons and brief conferences with the teacher. But what if that path to independent readers isn’t the most effective one? What if providing greater challenge, with more support, could lead to greater reading growth? My students and I had taken that second path. Inspired by research that suggests students could grow more through reading harder texts (once they had achieved about a second grade level of foundational skills) I have designed instruction to be teacher-guided and centered around texts that provide quantitative and/or quantitative challenges. But wait! you might be thinking. Isn’t there lots of research showing that students achieve the most growth when they read a lot of engaging, self-selected texts that are “just right?” (There are different formulations of what “just right” means, but it generally refers to texts that kids can read with 90-95% accuracy.) Well… not exactly. The idea that reading a lot of enjoyable, “just right” texts leads to reading growth seemed so intuitive that, for a long time, it didn’t get a good, sciencey workout. When researchers decided to study how text difficulty impacts learning, they found that reading more difficult texts (with scaffolds) either benefited students, or conveyed no disadvantage.** Despite the research, many teachers are still resistant to the idea of using texts that might be at what we deem “frustration level.” I mean, who likes to be frustrated? Recently, a few tweets* popped up in my Twitter feed that voiced these concerns. One Tweeter questioned “dragging” students through assigned texts. Another quoted an expert who said that hard tasks are disengaging, with the implication that maybe we shouldn’t do them. My experience teaching with complex text has not involved dragging anyone anywhere. I’ve found that, when you get it right, kids have a joyful experience reading and learning with challenging texts. Take, for example, a class of sixth graders at one of my previous schools. At that time, I was the literacy coach. Our curriculum began the year with sixth graders reading Rick Riordan’s The Lightning Thief, accompanied by the Greek myths the book is (loosely) based on. The teacher came to me for advice, because many of his students were recent arrivals in the U.S. and were learning English. The Greek myths, he said, were too challenging. I’d recently been reading some of the research on complex text and, even though it made us a little nervous, we decided not to take the route of finding lower-level texts for the students. Instead, we implemented a simple scaffold of chunking the text and providing focus questions for each chunk. With some practice, students began comprehending more of the text. At the end of the year, after a steady diet of challenging text, the students had grown 2.6 years in reading… and were huge Rick Riordan fans, continuing to read the series and grow their passion for reading. There are a few lessons I’ve learned about teaching with complex text:

If you want to try teaching with more complex text, but feel a little daunted yourself, try elevating the challenge bit by bit, testing out various scaffolds and seeing which ones work for you and your students. With a little bit of practice and the right texts, kids can experience the joy of doing hard things. *I’m not going to share a screenshot, despite the fact that some “science of reading” detractors do so in their blogs. Because… rude! **If you’re interested in why we can draw limited conclusions from the research that showed positive results with easier texts, most of it a) was either correlational or didn’t manipulate text difficulty as the experimental variable (i.e. you can’t make a causal claim about how text difficulty affects learning), or; b) the research measured the impact of text difficulty on comprehension, not learning over time. And when it comes to readers who are striving to grow, learning over time is critically important. ***If you look up Small Spaces’ Lexile, you’ll see that it is 570L – in the band for 2nd and 3rd grade. That is not particularly high in quantitative complexity for fifth graders, but its qualitative aspects – the horror plot, flashbacks, a book-within-a-book, literary allusions, and withheld information about key characters – make more appropriate for older readers. This is why it is important to keep both quantitative and qualitative measures of complexity in mind. It’s also worth noting that quantitative measures often underestimate the complexity of fiction and overestimate the complexity of nonfiction (due to elements like lengthy science terms). The lesson? Always read a text before selecting it, unless you want to accidentally scare the pants off some third graders while simultaneously confusing them with unconventional text structures.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Click the categories below for entries on specific topics.

AuthorCatlin Goodrow, M.A.T Archives

December 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed