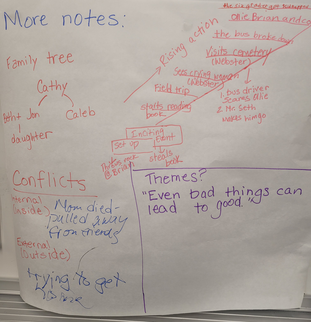

Our ongoing text map for Small Spaces. Our ongoing text map for Small Spaces. I was a few minutes late for my fifth grade reading group and rushed in, preparing to apologize to my students; I expected them to be sitting and twiddling their thumbs. Instead, one of the students had taken my usual place, passed out the books, and called on a peer to start reading. They just couldn’t wait another minute to dive back into the novel they were reading. I sat down in one of the chairs, picked up a book, and joined in. Later, we continued a lively, ongoing debate. The question: who was the terrifying “Smiling Man” in Katherine Arden’s Small Spaces? We were building a list of which characters might be the Smiling Man, and each student had their own personal theories. They added their thoughts to a sprawling text map we’d been keeping on sheets of butcher paper taped together. This excitement for learning is exactly what we hope for our students, and was in sharp contrast to the students’ attitudes at the beginning of the year. All five had been reluctant readers who claimed that reading was boring and dragged their feet when it was time to come to their reading lesson. For years, the conventional wisdom has been that we can spur reading growth and love of reading by providing copious amounts of reading time along with books that students can already read proficiently. Because, in this context, students are all reading different texts, the teaching comes in the form of generally-applicable mini-lessons and brief conferences with the teacher. But what if that path to independent readers isn’t the most effective one? What if providing greater challenge, with more support, could lead to greater reading growth? My students and I had taken that second path. Inspired by research that suggests students could grow more through reading harder texts (once they had achieved about a second grade level of foundational skills) I have designed instruction to be teacher-guided and centered around texts that provide quantitative and/or quantitative challenges. But wait! you might be thinking. Isn’t there lots of research showing that students achieve the most growth when they read a lot of engaging, self-selected texts that are “just right?” (There are different formulations of what “just right” means, but it generally refers to texts that kids can read with 90-95% accuracy.) Well… not exactly. The idea that reading a lot of enjoyable, “just right” texts leads to reading growth seemed so intuitive that, for a long time, it didn’t get a good, sciencey workout. When researchers decided to study how text difficulty impacts learning, they found that reading more difficult texts (with scaffolds) either benefited students, or conveyed no disadvantage.** Despite the research, many teachers are still resistant to the idea of using texts that might be at what we deem “frustration level.” I mean, who likes to be frustrated? Recently, a few tweets* popped up in my Twitter feed that voiced these concerns. One Tweeter questioned “dragging” students through assigned texts. Another quoted an expert who said that hard tasks are disengaging, with the implication that maybe we shouldn’t do them. My experience teaching with complex text has not involved dragging anyone anywhere. I’ve found that, when you get it right, kids have a joyful experience reading and learning with challenging texts. Take, for example, a class of sixth graders at one of my previous schools. At that time, I was the literacy coach. Our curriculum began the year with sixth graders reading Rick Riordan’s The Lightning Thief, accompanied by the Greek myths the book is (loosely) based on. The teacher came to me for advice, because many of his students were recent arrivals in the U.S. and were learning English. The Greek myths, he said, were too challenging. I’d recently been reading some of the research on complex text and, even though it made us a little nervous, we decided not to take the route of finding lower-level texts for the students. Instead, we implemented a simple scaffold of chunking the text and providing focus questions for each chunk. With some practice, students began comprehending more of the text. At the end of the year, after a steady diet of challenging text, the students had grown 2.6 years in reading… and were huge Rick Riordan fans, continuing to read the series and grow their passion for reading. There are a few lessons I’ve learned about teaching with complex text:

If you want to try teaching with more complex text, but feel a little daunted yourself, try elevating the challenge bit by bit, testing out various scaffolds and seeing which ones work for you and your students. With a little bit of practice and the right texts, kids can experience the joy of doing hard things. *I’m not going to share a screenshot, despite the fact that some “science of reading” detractors do so in their blogs. Because… rude! **If you’re interested in why we can draw limited conclusions from the research that showed positive results with easier texts, most of it a) was either correlational or didn’t manipulate text difficulty as the experimental variable (i.e. you can’t make a causal claim about how text difficulty affects learning), or; b) the research measured the impact of text difficulty on comprehension, not learning over time. And when it comes to readers who are striving to grow, learning over time is critically important. ***If you look up Small Spaces’ Lexile, you’ll see that it is 570L – in the band for 2nd and 3rd grade. That is not particularly high in quantitative complexity for fifth graders, but its qualitative aspects – the horror plot, flashbacks, a book-within-a-book, literary allusions, and withheld information about key characters – make more appropriate for older readers. This is why it is important to keep both quantitative and qualitative measures of complexity in mind. It’s also worth noting that quantitative measures often underestimate the complexity of fiction and overestimate the complexity of nonfiction (due to elements like lengthy science terms). The lesson? Always read a text before selecting it, unless you want to accidentally scare the pants off some third graders while simultaneously confusing them with unconventional text structures.

0 Comments

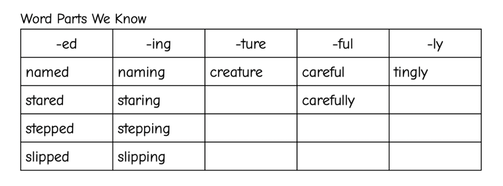

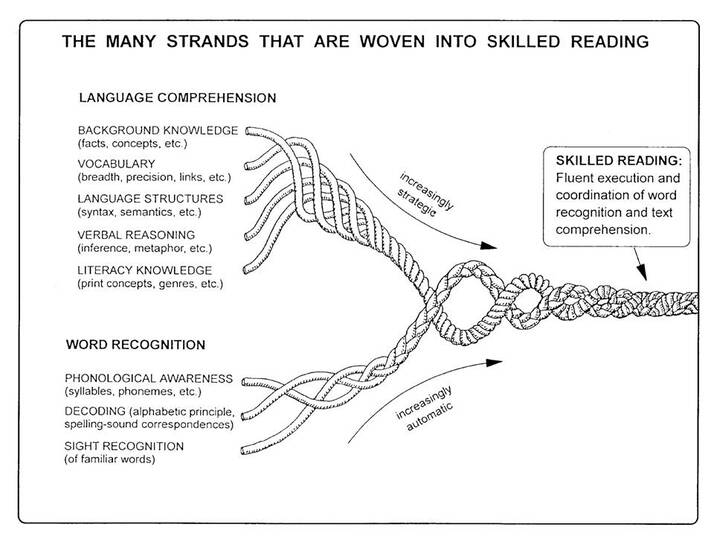

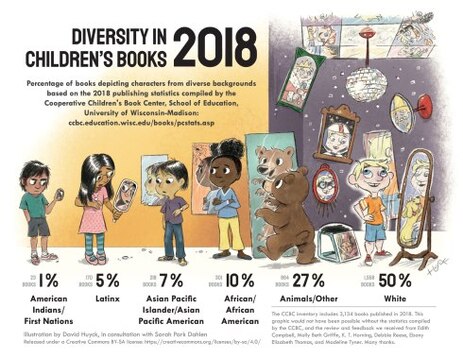

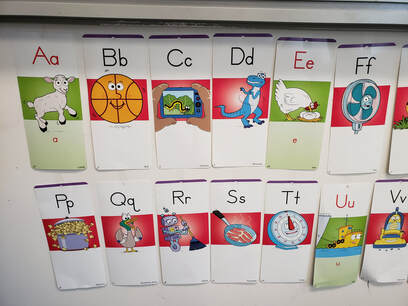

Well, it's nearly a new year, and in 2023 my resolutions are to do MORE of what I've been doing. More being the key word. This doesn't mean stagnation, but attempting to increase intentionality in everything I do. So what do I want more of? 1. More Morphemes Yes, I know it's a tongue twister. Morphemes are those meaningful word parts that allow English speakers to build upon a base word to create new words, such as carefully (care + ful + ly) or antidisestablishmentarianism (anti + dis + establish + ... well, you get the picture). Because English is just encrusted with words from many languages -- the way a tiara worn by Princess Kate* is encrusted with jewels -- English words may have bits and bobs from multiple sources, making it tricky for students to learn.. Explicit instruction in word parts supports students in both word reading and understanding word meanings (Carlisle 2010, in Manyak, Baumann, & Manyak 2018) In 2022: I added a morphemic element to the Word Previews my students do prior to reading. These previews have traditionally highlighted phonics patterns that students need to practice, culled from the pages they will be reading. This year, I built in more explicit instruction of word parts along with previews organized by morphemes (see example preview at right). In 2023: I plan to build more instruction of roots and affixes, building out our "Magical Morphemes" bulletin board so that it is a true resource for reading and understanding words (right now it is a sad little conglomeration of word cards.) As we read more nonfiction, I plan to strategically introduce roots that will support students in greater comprehension of science and social studies topics, building them into our Word Preview routine. 2. More Big Questions "Why were there so many rules?" Nadiia asked. Our small group had been reading about female scientists throughout history, and all of the women we read about chafed against the restrictions of their societies, whether in Germany (Maria Merian), England (Mary Anning), or India (Janaki Ammal.) The four girls in the group pondered what it would have been like to live in times when their lives were much more restricted than today, and the courage it took to "break the rules," as Aliyah put it. Generating questions is one of those strategies that the National Reading Panel (Shanahan, 2005) identified as supporting better comprehension. Too often, however, teachers are the ones who ask the questions. When we do, we limit students' attempts to understand, but we also limit their opportunities to make sense of the world, challenge the status quo, and engage more deeply in ways that matter to them. In 2022: I introduced the Cognitive Strategic Reading (CSR) routine (Klingner & Vaughn), which includes an after-reading question discussion. Students have been generating and discussing their own questions with lots of support. However, discussions have been somewhat cursory. In 2023: I plan to provide more explicit instruction on different types of questions, as well as strategies such as questioning the author or character. I also plan to build on their understanding of accountable talk to listen and respond to one another with more engagement. Students have the gist of the strategy, so it's time to go deeper. 3. More advocacy Currently, evidence-based reading instruction is a hot topic, thanks to the work of advocates and journalists, particularly Emily Hanford and Christopher Peak, who released the podcast Sold a Story this year. The podcast detailed how popular reading instructional methods fail many students. This has led to many a contentious Twitter convo and some real life drama in teacher's break rooms.. It has certainly led to some people being annoyed at me for my continued belief in continuously improving and adjusting our pedagogy to better align to research and to the needs of our students. (I know. Obviously I'm a monster.) In 2022: When several curriculum authors and professional development providers (many of whom profit from the methods discussed in the Sold a Story podcast) wrote a letter in response several teachers who have been acquainted on Twitter banded together to respond to the response... and then over 650 teachers and former teachers signed on to our letter. (A similar parent response received over 1300 signatures in support; there is A LOT of momentum for evidence-based instruction). Callie Lowenstein, who spearheaded our response letter, and I also contributed our thoughts to an article on the consequences of the pandemic on third grade readers. In 2023: I plan to revive this blog... during the pandemic, I admit, I didn't feel much like writing, and I wasn't in classrooms. However, after a year-and-a-half back in the classroom, I have plenty of thoughts on what it takes to put evidence into practice. I will always believe, in the end, that we have no excuse not to teach every child who is capable of reading, to be a skilled reader. It isn't beyond us. But it is a matter of having the will and the know-how to do so. *Kate wore said encrusted tiara to an event the same night Meghan Markle was told a tiara would be tacky. Coincidence? You decide! Curriculum Series, Part 3 Scarborough's reading rope (2001). Learn it, love it, sleep with a copy under your pillow. Scarborough's reading rope (2001). Learn it, love it, sleep with a copy under your pillow. Lately, I’ve responded to many questions, both online and in-person, about how to choose ELA curriculum. After all, it’s that time of year, when education leaders start thinking about the next school year and how they might improve student outcomes. (At least, I hope that’s what they are thinking about. They probably are not thinking that they have millions of dollars just lying around and new books might be nice. But you never know.) The curriculum selection process can be fraught—you want the best for kids, to make teachers’ lives easier, and to stay in budget. And even with a strong process, you’ll probably find that some people are just going to complain, no matter what you end up with. Still, I’ve learned a few things over the years that can help make the decision a little easier. Get grounded in the evidence In the past (and … probably today, let’s face it), curriculum selection looked like this: the district would put out a bunch of samples provided by publishing companies, invite teachers to look at them and give feedback, and then pick something that looked pretty or provided the best value. Those publishing reps are still out there with their samples, and a proliferation of online tools may catch your eye. With all those cute materials out there, it’s important to focus on what goes into skilled reading: decoding x language comprehension, aka the Simple View of Reading (proposed by Gough and Tunmer in 1986; you can find a good summary in the first third of this article). Scarborough’s “reading rope” (2001) further broke down each of those pieces. When you have the simple view in mind, looking at curricular materials becomes much clearer. Materials that don’t teach decoding systematically and explicitly, or don’t build language comprehension (which includes robust background knowledge), won’t give all children the opportunity to become proficient readers. There are many beautifully-packaged programs that do a bang-up job on one side of the equation, but not the other (and some that don’t do either well). You want to find materials that do both. Use free resources Finding a curriculum that teaches all parts of reading well may sound daunting, particularly if you’re a teacher or leader who has, you know, a few other things on your plate. Luckily, organizations have done the review work for us. EdReports and Louisiana Believes have some of the most complete reports on materials quality. Your state department of education may also have curriculum adoption materials available on their websites, such as rubrics or their own reports. However, be sure to crosscheck these with the sites listed above. I once did a curriculum review for a small charter school, and found that none of the curricula recommended by their state had been rated as aligned to the Common Core State Standards by EdReports. States often have other interests driving their decisions that go beyond educational best practices (as a recent New York Times investigation of textbooks showed). Put together a team Don’t deputize one person to choose the curriculum—and if you are the person who has already been deputized, this advice goes double. Put together a committee that will do the preliminary work of narrowing down choices to two or three, before presenting these to the broader group of stakeholders. Ideally, this team should consist of both new and experienced teachers, administrators, interventionists, and family or community members. Why include the community? Because they will be able to highlight the types of texts and experiences they want for their children. Many curriculum developers are actively working to increase the cultural relevance of their materials, but there is still much work to do in that area. By including community and families, you increase the chances of choosing curricular materials that will provide your students with both windows and mirrors. Make sure administrators are on board. No, really on board. I once participated in a curriculum selection process that was truly teacher-driven; in fact, teachers initiated the process and I supported them as literacy specialist. It was the sort of grassroots change that we often extol in education … and it was ultimately a failure, because even though administrators were brought into the process at various points, they didn’t have the deep understanding of reading science about how kids learn to read. Both your committee and all administrators need to be grounded in what makes great literacy teaching, particularly as this can look much different from the standards-based, skills-focused teaching that works in many other subjects. Unless administrators are prepared to work shoulder-to-shoulder with teachers in implementing a new curriculum, things can get very messy, very quickly. While there’s no easy way to find the right curriculum for your school or district, having a strategic, inclusive process will help set a firm foundation for the really fun part … implementation! (Coming up!) Note: This is the third (really, the fourth) in a series on the practical side of implementing high-quality curricula. Part 1: The Power of a Quality Curriculum Part 2A: Assumptions Part 2B: Another Assumption Part 2C: One More Assumption Part 3: Choosing a Quality Curriculum Curriculum Series, Part 2C: The Third Assumption Every kid deserves books that will challenge them and take them to new places! Every kid deserves books that will challenge them and take them to new places! It’s time to discuss the final assumption that holds many schools and districts back from implementing high-quality curriculum: the belief that challenging, on-grade-level reading curricula are too difficult for many of our scholars, particularly those who are reading below grade level. I have come across this assumption many times, particularly when teachers look at the texts and tasks for a new curriculum the first time. They may think of particular students who have struggled, and feel that the curriculum is "above" the level at which their scholars are able to achieve. I have even heard teachers say, "This is a good curriculum for schools where all the kids are on grade level, but not for my students." This was said out of a desire for students not to struggle, rather than malice ... but as we'll discuss, trying to keep scholars from difficult challenges doesn't help them. This sentiment isn't restricted to certain locales, so I asked Robin McClellan, Supervisor of Elementary Education at the Sullivan County Department of Education, to help me out with this installment. I’ve seen what high-quality materials meant in my tiny district last year (first graders were above 90th percentile for growth on NWEA MAP, woohoo!), but wanted to hear from a larger district about this issue. Robin’s words are in italics throughout the post. (Before I jump in, though, let me share that Robin and I met on Twitter. If you want to meet cool people interested in the science of reading, and join a lively conversation every Wednesday from 8:00 p.m.-9:00 p.m. EST, follow @elachat_US or jump in with #ELAchat!) Now, here’s Robin: As attention builds around the national reading crisis (not new but our moral imperative to fix), districts must provide teachers with high quality instructional materials (HQIM) as the foundation to their literacy practices. Our district is demonstrating quantitatively and qualitatively that strong materials are one half of the equation for progress; the other half being spiraled support and a collaborative culture, leading to teacher efficacy. Yet, critics assert that often HQIM are “developmentally inappropriate” or are too difficult for students already demonstrating gaps. I say...not so. Our teachers agree. In November, I observed a group of fourth grade students making connections between King Arthur’s insistence on the use of a round table (equality) to the civil rights movement as depicted in Brown Girl Dreaming (inequality). This is an example of the kind of thinking scholars can do when challenged. Robin found that all children in the classroom were able to make those connections, regardless of reading ability or background--in fact, it was impossible for observers to tell who might be reading below grade level. As discussed earlier in this series, however, large numbers of students throughout the U.S. are regularly being assigned below-grade-level work (TNTP, 2018). There is a belief that children should be reading at their “independent” or “instructional” levels, and that frustration will result in destroying the love of reading. This common practice, while intuitive, is based on a 1946 textbook, which itself used flimsy evidence! (Shanahan, 2011). More recent research suggests children actually learn more when reading harder texts … as long as scaffolds are in place (Brown, Mohr, Wilcox & Barrett, 2017). High-quality materials both provide complex, grade-level texts and give teachers ideas for how to support students in using these materials. The result? Here’s Robin again: In our district, the numbers match the qualitative picture. In 2018-2019, at EVERY grade level, our elementary schools saw a decrease in the percentage of students scoring “at risk” for not meeting grade level standards (as measured by AIMSWEB) throughout the course of the year. In the early grades, as a district,

This quality instruction for all children has the added impact of helping us to truly identify those students who really need additional interventions. When children receive instruction that is not evidence-based, it’s difficult to know the root causes when children struggle. Having confidence in our instruction means that we are less likely to over-identify children for additional support, saving resources and time … and simply making the school experience more equitable. And that is what all children deserve. Or to put it another way: This translates to a very direct and compelling message that HQIM narrow achievement gaps. As teachers dive into the specific needs of students and use data to fill in skill gaps as they surface, it is the perfect storm to build proficient readers. Note: This is the third in a series on the practical side of implementing high-quality curricula. Part 1: The Power of a Quality Curriculum Part 2A: Assumptions Part 2B: Another Assumption Part 2C: One More Assumption Part 3: Choosing a Quality Curriculum Part 4: Implementing a Quality Curriculum (Coach/Admin Edition) Part 5: Implementing a Quality Curriculum (Teacher Edition) Curriculum Series, Part 2B: Another Assumption In which, dear reader, I continue to examine assumptions that hold districts and schools back from adopting high-quality curricula. The first assumption is here. Now ... Assumption #2: providing a curriculum disrespects teacher expertise/ teachers don't want or need a curriculum provided to them. My friend Kelly loved the principal at her first school, yet she left that building for another. Why? Her best friend was teaching at a school that used a structured literacy curriculum, and the kids were taking off as readers. Kelly wanted that for her students. She asked her principal to consider letting her use the same curriculum. “I don’t believe in teaching reading out of a box,” he said. So Kelly left and got a job at the same school as her friend. Her principal lost one of the best teachers I’ve ever seen in the 200+ classrooms I’ve visited all over the U.S. The principal’s belief—that providing teachers with a curriculum is “teaching out of a box”—is a common one. Writes Kathleen Porter-Magee (2017) “In education we have been conditioned to believe that mandating curriculum is akin to micromanaging an artist.” This point-of-view can lead districts to think they are doing teachers a favor by giving them unlimited “autonomy.” Even when lack of resources drives teacher dissatisfaction, as it did for my friend Kelly, we rarely talk about the positives that a strong curriculum can have, not just for students, but for teachers and their experiences. Providing teachers with high-quality materials can save them both time and money. A RAND study (2016) recently found that teachers rely heavily on materials that they develop or select themselves (99% of elementary ELA teachers do this, as well as using tools they’re provided). Teachers spend more than 12 hours per week on this work (Goldberg, 2016, cited in EdReports.org). Writes Robert Pondiscio (2016) “For teachers, it [having to develop their own curriculum] makes an already hard job nearly impossible to do well.” It also means that teachers often end up spending their own money to make sure they have the teaching resources they need. Doing such planning for ELA can be particularly time-consuming (well beyond twelve hours a week). When I’ve worked in curriculum development, I’ve often spent hours finding the right text for a lesson or assessment. When the right thing hasn’t been available, I’ve written pieces myself. This was my full time job, not something I had to do in the evenings on top of teaching a full day of classes. Requiring this work of teachers can help accelerate burn out, particularly for those new to the field. It’s likely this time crunch contributed to the fact that teachers identified “high-quality instructional materials and textbooks” as their NUMBER ONE (well, tied for first) funding priority in a Scholastic survey. It’s notable that materials didn’t even rank in principals’ Top 5 funding priorities, signaling a real disconnect in what teachers and leaders see as important. Principals and leaders may want to dig deeper if they believe teachers don't want or need high-quality resources. Another reason teachers may want high-quality materials? Shared resources can lead to robust, powerful collaboration. For example, when Detroit schools adopted EL ELA curriculum and Eureka Math, not only students showed growth--but teachers grew as well, through coming together in professional learning communities (Higgins, 2019) in which they supported one another through the curriculum shift. Some of those leaders then went on to support the teachers in Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools (EL Education, 2019), and in partnership with EL have shared free PowerPoints that can be used by teachers anywhere. Collaboration has even branched out nationally - check out the Facebook group where teachers are sharing their insights about EL curriculum, pointing each other toward resources (like those PowerPoints), and providing support through both excitement and challenge. I experienced this when I was moved into a first grade classroom in February of last year when a teacher unexpectedly left the school. There was no prescribed curriculum for first grade, so my partner teacher and I decided to start implementing EngageNY math and EL ELA curriculum. Our collaboration became much richer than it had before--no longer were we racing to find materials on the internet or designing new lessons. We were asking: how did that lesson go? Who got it? Who needs more support and why? How did you tweak this? Although we were two of the most experienced teachers on campus, having a curriculum didn’t bog us down or steal our creativity. It empowered us to focus on our students in an even deeper way. Finally, high-quality curriculum can build feelings of efficacy when we see our kids achieving at high levels, our districts improving, and our work paying off. This was why my friend Kelly ultimately had to leave her first school -- to grow into her best professional self. Her curriculum helped her to build capacity, and she became a stronger teacher for it. Check out this incredible thread (especially the inspiring videos from @kyairb) for more examples of how powerful curriculum can play out for kids and teachers. Says @kyairb: "Absolutely. Your kids can do it.... I'm a really good teacher. I know what I'm capable of doing, and I know that I'm capable of committing myself to a curriculum that builds knowledge." Resources, collaboration, feelings of efficacy ... sounds great! Despite the positives that a curriculum adoption can bring, many teachers still find curriculum change to be a miserable experience. This is often an issue of implementation, rather than the curriculum itself. I’m going to write more about what I’ve learned about implementation later in this series, but I did want to mention one thing. Too often, teachers feel disrespected during curriculum change because there is a focus on fidelity to the curriculum without honoring the lived experience of teachers and their students. Take one example: Several of my friends worked at a charter network where they were given a high-quality curriculum with interesting texts and lots of support; no deviation from the script was accepted. Implementation was a constant source of frustration. One of my friends was the lead teacher and was still evaluated on her fidelity, rather than effectiveness. She wanted curriculum and feedback to help her grow, but she didn’t want to simply become a script reader. While it’s important to implement a new curriculum without diluting its power, there is an alternative to ”fidelity:” integrity. Writes Paul LeMahieu (2011): “This idea of integrity in implementation allows for programmatic expression in a manner that remains true to essential empirically-warranted ideas while being responsive to varied conditions and contexts.” In other words: you keep the well-researched practice in the curriculum, while using your knowledge of context to maximize the impact of the curriculum and make it relevant for your students. If we keep our focus on implementation with integrity, we can experience the benefits of high-quality curriculum without many of the downsides that cause people to fear “teaching out of a box.” Note: This is the third in a series on the practical side of implementing high-quality curricula. Part 1: The Power of a Quality Curriculum Part 2A: Assumptions Part 2B: Another Assumption Part 2C: One More Assumption Part 3: Choosing a Quality Curriculum Curriculum Series, Part 2A: Assumptions November 6th, 2018—the 4th grade classroom was abuzz with discussion as students took turns at the mock voting booth, deciding whether Beto O’Rourke or Ted Cruz should be our state’s senator—just like adults were doing down the hall.* The classroom was hung with posters advocating for voting, and a stack of essays sat on my desk, arguing why voting was important. When the assistant principal came in, the students were eager to tell her how many Americans didn’t vote, and why that surprised them, given the long fight for suffrage for women and people of color. You might assume that kind of real-world, time-embedded teaching couldn’t be done with a district-mandated curriculum. But of course (spoiler alert), it was. The RAND Corporation (Kaufman, Tosh, & Mattox, 2019) recently found that only 7% of elementary ELA teachers are regularly using high-quality curricular materials. Why is that? Over the past several years advocating for curriculum changes, I’ve heard all kinds of push back to adopting these curricula, much of it based on assumptions about instituting centralized curriculum. The three that I have encountered most? 1) A centralized curriculum is boring/irrelevant; 2) Providing a curriculum disrespects teacher expertise; and 3) Common Core-aligned curricula are "too rigorous" for our striving readers. I kept hearing these things as I worked to change our district’s literacy practices, and I began to doubt my advocacy for this change. I decided I had to pressure test some of these assumptions myself. So, after 11 years of coaching and literacy leadership, I spent a year full-time in the classroom. I ended up teaching fourth and first grades, each for about half a year (due to one of those shake-ups that tend to happen when a staff member leaves suddenly). In this post and the next, I’ll share my thoughts about what I’ve learned about these three assumptions. What I Learned About Curriculum, Relevance, and Representation First, let’s address the white elephant in the reading room: children’s literature has a long way to go before the characters look like the kids in America’s schools. While approximately 51% of public school students are children of color (NCES, 2019) the number of characters of color in children’s literature stands at 23% (CCBC in Huyck & Dahlen, 2019)--fewer than the percentage of animal/other characters. This weakness impacts curricular materials, of course. The Coalition for Educational Justice (2019) looked at ten popular curricula and book lists used in the New York City area, including several that are highly-rated for standards alignment on EdReports. They examined the number of texts by authors of color, as well as the characters on text covers. They found a situation slightly better than the publishing world at large, with 33% of cover characters representing children of color, 35% White children, and yes … 32% animals. Representation was particularly low for Latinx, Asian, and Indigenous characters. This means that no matter what teaching methodology we ascribe to, as teachers we need to keep searching for ways to make our teaching more culturally relevant. However, the study linked above found that some of the weakest representation of children of color was found in the curricula or booklists that are often used by teachers who focus on teaching through students’ self-selected reading. High-quality curricula can get us started from a slightly stronger place than relying on the classroom library the district purchases for us. In addition, many of the developers of newer curricula have student interest and relevance on their minds. For example, the folks at Great Minds were willing to work with Baltimore City Schools to increase the relevance of their With & Wisdom curriculum to better connect to the community (Loftus & Sappington, 2019). Open Educational Resources (OER) are free and online, allowing developers to be more responsive to users’ needs. Often, these resources are adaptable for teachers who want to tailor instruction to reflect their students’ communities and identities. It was through the use of an adaptable OER that I was able to craft the election day experience in my fourth grade classroom. Our module centered on creating change, with a focus on battling for suffrage. I had planned a similar unit from scratch during the 2004 presidential election, but having the foundation of a trustworthy, high-quality module made the planning easier. Because the scope of the module had been laid out, I was able to look through the entire thing and determine where I wanted to add or subtract material to increase representation and relevance. Given that most of my students were Latinx, many born in Mexico, it was critical to connect to the political events of the day, which we often discussed in class. We identified issues the students cared about, then read quotes from the Senate candidates so students could determine who they would “vote” for. On election day, they were knowledgeable about the most important issues facing them in a way that wouldn’t have been possible without the rich knowledge built through the curriculum. Having that framework also gave me the time to plan to connect the lessons to my students in a way that I wouldn’t have been able to if I’d had to scramble to find materials and texts. So, yes, standardized curriculum can be relevant and engaging … when the teacher is allowed the freedom to tweak the lessons, and has the knowledge to keep the integrity of the program’s alignment with standards and research. And that has to do with implementation… more on that coming up soon. * The kids picked Beto in a landslide. This is the second in a series on the practical side of implementing high-quality curricula. Part 1: The Power of a Quality Curriculum Part 2A: Assumptions Part 2B: More Assumptions Part 3: Choosing a Quality Curriculum Part 4: Implementing a Quality Curriculum (Coach/Admin Edition) Part 5: Implementing a Quality Curriculum (Teacher Edition) Notes: Note 1: I had planned ONE post on curriculum assumptions, but this one ended up being a bit longer than I intended. I’ll address two more assumptions coming up. Note 2: I had originally planned to talk about curriculum “myths,” but decided to change to “assumptions” because myths implies these beliefs aren’t true. I think these assumptions do have seeds of truth in them -- it’s just that the seeds are planted through implementation issues, rather than by the curricula themselves. Implementation will be coming up. Note 3: That cool graphic is free to use through the Creative Commons License, as long as the full citation is provided. Here’s the full citation! Huyck, David and Sarah Park Dahlen. (2019 June 19). Diversity in Children’s Books 2018. sarahpark.com blog. Created in consultation with Edith Campbell, Molly Beth Griffin, K. T. Horning, Debbie Reese, Ebony Elizabeth Thomas, and Madeline Tyner, with statistics compiled by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center, School of Education, University of Wisconsin-Madison: http://ccbc.education.wisc.edu/books/pcstats.asp. Retrieved from https://readingspark.wordpress.com/2019/06/19/picture-this-diversity-in-childrens-books-2018-infographic/. Curriculum Series, Part 1 [Meme showing LeBron James. "You say you care about outcomes, but your curriculum is from Pinterest."] [Meme showing LeBron James. "You say you care about outcomes, but your curriculum is from Pinterest."] This is the first in a series on the practical side of implementing high-quality curricula. Part 1: The Power of a Quality Curriculum Part 2A: Assumptions & 2B: More Assumptions Part 3: Choosing a Quality Curriculum Part 4: Implementing a Quality Curriculum (Coach/Admin Edition) Part 5: Implementing a Quality Curriculum (Teacher Edition) When I was a kid, my family moved a lot. I went to four different schools between kinder and 4th grade. I remember coming home one day from that fourth school, and telling my mom, “We’re learning about bees again. Why do we study bees every year?” You see, I was under the logical (yet, false) assumption that someone (maybe the president?) had determined what a kid should learn every year -- and that bees only needed to be studied once in elementary school. Don’t get me wrong, bees are fascinating. It’s just that there are other insects deserving of study -- not to mention all the other animals. I know a lot more about education now, but as Natalie Wexler points out in The Knowledge Gap (2019), our educational standards describe many processes, skills, and strategies that students are supposed to learn, but are vague on the content that students should be processing and strategizing about. That’s where having a high-quality curriculum can shine a light. When I say “high-quality” curriculum, I am talking about those literacy curricula that align with the current best evidence about how children learn to read. These curricula are explicit and systematic in teaching decoding, and they intentionally build world knowledge. They also avoid teaching counterproductive strategies, like the three-cueing system. (Check out edreports.org for more information about excellent curricula.) Such curricula are powerful in a way that the old-school basal programs were not. As a literacy coach, curriculum coordinator and teacher, I’ve seen three main ways that power manifests: A high-quality curriculum is coherent. What my little fourth grade heart desired was coherence -- a curriculum that put a stake in the ground about what should be learned each year, how that knowledge should build, and how it all links together. According to cognitive scientist Daniel Willingham (2006), that coherence isn’t just elegant, but helps us learn: “A rich network of associations makes memory strong: New material is more likely to be remembered if it is related to what is already in memory.” A colleague and I saw this in action last year, when we tested out a module from the EL Education first grade curriculum. The module topic was sun, moon, and stars. Because of the coherent, systematic knowledge-building, our first graders were able to articulate deep understanding of why we have day/night and seasons. These same concepts were ones that our fifth grade students were struggling to comprehend in science class. A high-quality curriculum also drives equity. Recently, TNTP (2018) found that out of 180 hours of instruction, 133 hours are spent on activities that are not on grade level. Almost 40% of the study classrooms with a majority of students of color had NO assignments on grade level, compared to 12% of classrooms with a majority of White students. This is, frankly, appalling. However, many teachers aren’t given the resources to align their instruction to a high bar of excellence. For example, I witnessed a lesson in which the teacher followed the district-provided curriculum, trusting that she was given a quality resource. The curriculum did not align to grade level standards for complex text, and one of the second grade vocabulary words was basketball. Compare that to vocabulary words in a highly-rated, Common Core-aligned curriculum for second grade: compassion, visible, and respond. In which classroom would children be on the road to being college- and career-ready? Finally, a high-quality curriculum can build teacher capacity. A colleague of mine says, “Teaching a good curriculum is the best professional development.” It can help us understand standards, teach us new pedagogical methods, and introduce us to new texts and topics. More importantly, it can shift the teacher’s time and focus away from scrambling for materials, to diving deep into lessons and considering how students will be impacted. We can unleash this power in classrooms throughout our country. However… a series of myths about curriculum persist. I’ll discuss those in Part 2.  Let’s imagine that one of your most knowledgeable, trustworthy friends came up to you and said: “I just read a bunch of reputable research that said eating vegetables isn’t healthy. In fact, these studies say that broccoli and carrots are harmful and we need to eat more chocolate!” Even if your friend showed you the studies, the graphs, the testimonials from former veggie-lovers who had seen the light; you’d probably still believe vegetables are healthy. After all, if you could have been eating chocolate all this time, why did you waste years on salads? In fact, you’d be likely to dig in your heels and chomp on even more veggies than before. This is because, when we are devoted to a certain truth, we tend to ignore contradictory evidence and seek out confirming evidence. We become more committed to our beliefs, which is known as confirmation bias. Confirmation bias is why arguing with your grandma about politics is futile, even when you have the facts on your side. Sometimes, though, confirmation bias can have higher stakes than hurt feelings at granny’s. When evidence tells us that we should rethink our teaching practices, we educators can be more stubborn than your Uncle Leo repeating talking points he got from Sean Hannity. Even if -- especially if -- evidence might suggest we could have been doing better for our students all along, we’ll argue that what we’ve been doing is “best practice.” I’ve been thinking about the difficulty of changing practice a lot lately, because the past few weeks have seen a series of earthquakes in the literacy-teaching world. With the release of Natalie Wexler’s book, The Knowledge Gap, and Emily Hanford’s audio documentary, At a Loss For Words, it could feel like everything we’ve been taught about teaching reading is wrong. That’s when our confirmation bias protects us by screaming that we should go read something that supports our past practices. After all, change is hard. It might not be favored by our bosses, might need resources or knowledge we don’t have. But the deepest reason not to change? It feels terrible to think we could have been doing better by the students in our charge. But if we’re truly committed to providing the best education possible, we have to change as we learn. A the saying goes, “know better, do better.” So, how do we overcome our confirmation bias? How do we start to change, even when it hurts? Below, I share a few tips that have helped me and others (with a few insights into my own biases and mistakes along the way). 1. Seek out perspectives other than your own. Brooke Gladstone, of NPR, puts it this way: “You have to vary your media diet a little bit, like read something that you just wouldn’t be inclined to read.... And keep taking in their perspective. It’s incredibly helpful to just know what’s going on in the world.” This process, she admits, can be painful. However, it can be necessary in expanding our awareness. For years, I admit I’ve had a bias against private school vouchers. Studies have shown that my bias was reasonable. However, listening to parent education advocates explain the reasons they want vouchers has made me more aware of my bias and more open to considering other perspectives. 2. Take a cue from Marie Kondo. De-cluttering expert Marie Kondo suggests that it can help us let go of unwanted clutter by thanking items before we discard them. When it’s time to let go of teaching practices we’ve learned are less effective, we can be grateful for their utility when they were the best we knew. Reading Wexler’s book, there have been several times when she has presented research that counters something I did in my own classroom (or even -- yikes! -- shared with other teachers as good practice.) Yes, it can make me feel guilty. I move past that by telling myself: “It was the most effective thing I knew to do at the time, and now I can do something even more effective.” Staying in the guilt of our past doesn’t help our students, nor does ignoring new evidence. 3. Change your thought pattern. Cognitive therapists help people overcome challenges by reframing their self-talk. Making small changes in the way you think can change your practices in big ways. For example, although I’m a believer in phonics, when I became exasperated with a student’s attempts to sound out a word, I would sometimes ask them to look at the picture to figure out the word -- even though I had learned this was ineffective, even counter-productive. So I changed my thinking with a short phrase. Whenever I was tempted to encourage a student to guess, I said to myself, “We don’t guess. We say the sounds.” By picking a short, positively-framed phrase I could repeat to remind myself of the change I wanted to make, I altered my self-concept to that of someone who wouldn’t resort to a shortcut. Change can be painful, and our brains want to protect us from that pain with confirmation bias. For our students, however, shifting our thinking is critical to helping them succeed.  Lately, there’s been a renewal of “the reading wars” -- in part due to a couple of high-profile pieces in the media about the lack, in some schools, of systematic phonics teaching (here and here). If you’re not familiar with the Reading Wars, which crop up every few years, the gist is an argument over the best way to teach reading. I won’t go into all of the details here, but this is a good summary of some of the key issues and timeline, if you’re interested. One of those issues is whether all students should get explicit, systematic phonics instruction. Some educators, rightly, state that not all children need direct instruction in phonics. Those students will learn to read without this instruction. Advocates of less-systematic phonics instruction would argue: Why waste time on instruction that kids don’t need? However, as a teacher and teacher-educator I believe in explicit, systematic phonics instruction for all children in grades K-2 -- and for those in higher grades who need it. Timothy Shanahan recently wrote a great blog post from a research perspective on why teaching phonics to all students is beneficial. But what about the teacher perspective? Why do I teach phonics to all students? 1. I teach phonics because it helps kids learn to read. I mean, this seems like an obvious reason. First-grade teachers who teach systematic, explicit phonics often describe the “January miracle.” That’s when, suddenly, students who weren’t reading are tearing through texts. This past year, I took over a first grade classroom when a teacher had to go on leave. My students hadn’t been getting consistent instruction in the fall, so the January miracle came around March. By the end of the year, my students had shown NINE MONTHS of reading growth in four months, and were in the 91st percentile for growth on a nationally normed assessment. Of course, phonics wasn’t all we did. Phonics should never be the only reading instruction - a phonics program is not a literacy program. However, my class focused heavily on cracking the code, and it showed. 2. I teach phonics because it builds the love of reading. The most consistent argument I hear against systematic phonics instruction is that it somehow crushes the love of reading. Tell that to my student, Bisael, who would happily shout, “Miss, we’re getting the hang of this!” whenever the class met a new reading challenge. My students obsessed over the set of decodable books I’d found in my classroom, to the point that I sometimes had to say: “I’m happy you love reading, but I’d like you to take a little more time on your math assignment.” Being able to read the words of a text is the first stop in loving to read, and students who struggle are often those who “hate reading.” I suspect that those who don’t equate phonics with loving reading have experienced some boring phonics lessons. But just because something is explicit and systematic, it doesn’t mean it has to be boring. Short, snappy, and clear lessons keep kids engaged and learning. 3. I teach phonics because it’s interesting -- to my students and to me. Can you easily explain why A says one sound in apple and another in apron? Why do some words have a silent gh? Have you ever said to yourself: “English is just weird.” If these thoughts resonate with you, you are thinking about phonics! English is more regular than most of us suspect; it’s just that the regularity is complicated and deeply embedded in the way English has evolved over the years. Sharing this complexity with students is a constant challenge and has so many levels that even those students who “don’t need” phonics can learn fascinating things about the history of our language through phonics. 4. Phonics helps you crush crossword puzzles. Trust me on this one. Coming up: How I Teach Phonics This is my superhero origin story.

In my teacher training courses, I'd learned about pedagogies that warmed the cockles of my hippie girl heart: reading workshop, guided reading. These methods rely heavily on students reading "just right" books, often of their own choosing. What could be better? When I got to my campus, however, I found that I was going to be using SRA Open Court Phonics, a direct instruction program in letter-sound correspondence. Even as my mentor teacher assured me that kids would be reading by January, I remained skeptical. This skepticism wasn't based on any research or knowledge of how kids learn to read. I just didn't like it. I had to admit, the kids seemed to enjoy the rapid-fire, explicit lessons, which were accompanied by a puppet lion. (The furry puppet was much too hot for the Houston weather, and so he went on vacation to the "puppet hotel" and had so much fun he never came back.) I found the whole practice stultifying, at odds with the progressive practices I'd learned about and my own vision of who I would be as a teacher. I swore that if I had a choice, I would teach a different way, even as my students learned to read. After my first year, I taught summer school at another campus that had not used the program. I was astonished that, every time they came to a word they didn't know, my new students simply looked at me. "Say the sounds," I said, a prompt that would have had my own students using their letter-sound knowledge to begin blending the word -- although my kids didn't need much prompting by the end of the year. Still, my summer students looked at me blankly. I realized: they didn't know the sounds letters make. And therefore, they could not attack unfamiliar words with meaningful strategies. That was it for me. I went back to my campus in the fall with a new belief in the power of direct phonics instruction. I never looked back. |

Click the categories below for entries on specific topics.

AuthorCatlin Goodrow, M.A.T Archives

December 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed